“The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one’s self.” –Igor Stravinsky

Structure is lovely. Who doesn’t enjoy the calm of symmetry, the excitement of following an unfolding pattern? It’s as true in architecture and tapestry as it is in music and poetry. Even the departure from form can be, itself, a kind of plan or process: here’s how the artist fulfills an expectation, here’s how he breaks one. The dissonance in the harmony. Good art can draw from disparate source material; it can recreate past themes or innovate greatly. It can surprise us, but it is not random.

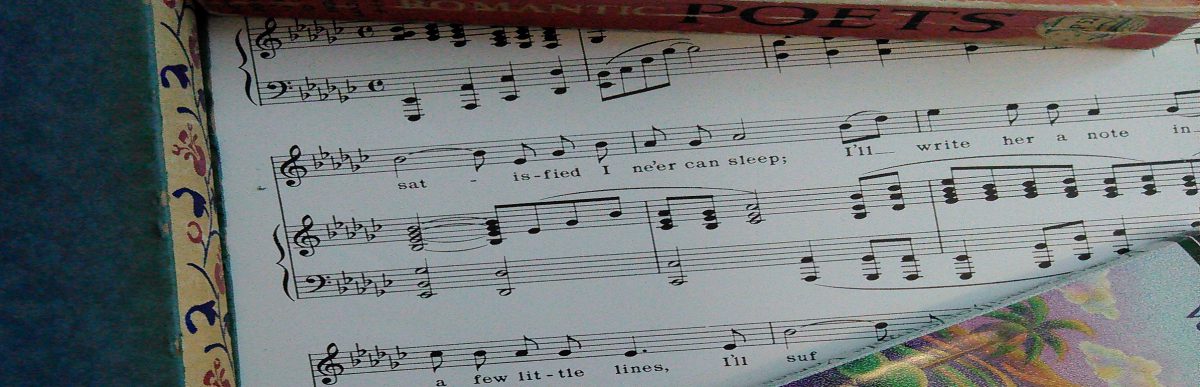

As part of my autodidactic poetry work, I’ve tried composing in various classical forms. There was the sonnet to a college boyfriend (Shakespeare I wasn’t). The villanelle (same form as In Flanders Fields). The sestina. Composing within these structures reminded me a lot of learning to compose music. As a kid taking piano lessons, I had assignments to complete eight-bar phrases or write variations on a given theme. The idea was to learn guidelines of what made musical sense, e.g. you need the same number of beats in each bar; you mostly end on the tonic, that sort of thing. Breaking the “rules” of the form could result in something funny-sounding, or cool-sounding, at times. But I understood even that young that the point was to be able to converse musically—to show that you had the skill to play the game. Students of any art who have a grasp of structure are better at improvising, and more skillful at breaking conventions with a purpose in mind, than students who are completely unlettered. In college we analyzed Bach chorales and composed our own, according to the rules of Western tonal harmony. Parallel fifths were verboten, likewise doubling the leading tone. It was interesting to see how often the great composers broke the “rules” to which we students had to adhere. But again, there were reasons why they did—why their part-writing yielded a more compelling whole with the nonconforming bits in there. Looking at poetic form, one makes the same observation: in the sonnet, the rhyme scheme is such-and-such, except when it isn’t. In a ballad, the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables is thus-and-so, except when it isn’t. The “when it isn’t” usually is the most interesting part, but it couldn’t exist effectively without the surrounding steadiness of the expected form.

Musical forms and poetic forms are, traditionally, different. Classical piano forms (or, sometimes in the literature, “styles”) include the sonata, the rondo, the minuet and trio, the invention, and the fugue. The structural elements deal with time—numbers of beats and bars—as well as motif, or how collections of notes are presented and developed into musical ideas. One other important element is tonality, which plays out through time and pitch. A typical thing for a composer to do is open a piece with a catchy bit of melody or a few strong chords: a main idea, or motif. Then the composer goes on to repeat and vary that motif, lengthen, shorten, and elaborate on it, imparting some sense of unity to the piece through timing and harmony. (I’m purposely not dealing here with chance or aleatory music, or free improvisation, but I’m not claiming that those categories of music can’t have structure too.) Poems don’t work in that many dimensions at once. But we use the same quick system to describe poetic rhyme scheme that we use to outline musical form: just big capital letters. So a poetic quatrain goes ABAB, and a binary-form keyboard minuet goes AABB. So a terza rima poem goes ABA BCB CDC, and a keyboard rondo goes ABACABA. (There’s also a poetic form called the rondeau, pretty different, very cool.) It’s not as simple as snapping component parts together, or not if you want a poem with any depth. And it would be a stretch to suggest that poems and music could take each other’s forms. And yet.

We know that poems and music can both fulfill formal expectations. We know that both proceed from what coalesces in the mind and falls upon the ear. It all led to me wonder whether a musical form could be used as the mold for a poem. I invented (as far as I’m aware) a form that I call the keyboard rondo. It’s a poem of several stanzas—number of stanzas not predetermined—in which each stanza has the rhyme scheme ABACABA, which, as I mentioned, is the formal structure of the musical piece known as a rondo. Timewise, a Mozart or Beethoven rondo is going to take longer to unfold than one of my poems, because each of those capital letters represents a section of music, rather than one line of text. So, the poem form I invented is a microcosm that repeats, within itself, the structure of the macrocosm. I wanted a musical form to hold thoughts about music, so it seemed an appropriate linkage.

Here’s a rondo where I try to have word-by-word discipline while writing about the acquisition of piano technique, and falling somewhat short both inside and outside of the poem.

Keyboard Rondo III (Albumleaf)

How many different saints you’ve been

and how often betrayed.

How various the kinds of din

you’ve borne in silent thought.

Each time I play, almost, a sin

and my damnation stayed

by your corrective mercy listening in.

Sometimes I cough up notes, as ill

as anyone who has bronchitis.

It shouldn’t be like phlegm, or fill

my head with pounding pulse,

I know, and you remind me, still

upon your bench as Christ is

on his cross upon the hill.

Other days are better, the trill

tweedles out between lean fingers

that hardly seem mine, and no more will

is needed to play than desire.

Then all is temperate, nothing shrill

or gurbled, nothing lingers

after the pedal echoes to nil.

Until recently, the rondo was the only classical music form I consciously tried to imitate in poetry. Last month I wrote a short piece based on the idea of the etude, or study. In music, an etude can be a piece of any length meant to teach or reinforce one musical idea or technique. If you’re a brass player, you practice partials etudes, getting your lips and air to cooperate in producing different notes with the same fingering. If you’re a flutist, there are plenty of trill and turn etudes, refining those ornamental groups of notes. If you’re a pianist, you study Hanon and Czerny for speed, fluency, and coordination between the two hands. For my poem/etude, I explored the idea of the fifth, broadly defined: the dominant note of a scale; a “perfect” interval between two notes; a bottle of whiskey, and even the number five as relates to counting, for example in the Dave Brubeck tune “Take Five” (which also begins on the fifth note of the scale). The title is a pun on “Solitude,” the Duke Ellington tune made memorable by Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, and Louis Armstrong.

Sol Etude

I’ll arrive soon, see you

in five, schedule up

in the Airegin. Don’t count

on Brubeck or Rollins, fly there on

my own time, in my alone

time, don’t count on the Duke,

C Jam Blues has an open secret. Same

as Bingo, Happy Birthday, Auld Lang Syne:

home isn’t where you start, perfect, but

where you, broken, end. Work’s not what you’ve

done, it depends on repetition-love

and liminal lines. If tonic

is a drink

for the health, a mixer

for something strong then

swallow

straight.

If a fifth is

what you sip at

don’t wait, screw

the cap back on

or swig it

down, i.e. fish

or cut bait.

As I rambled through my music form exploration, I discovered that some poets had gotten here before me. Specifically with regard to adapting song (and dance) form to poems, drawing on the black American heritage that includes spirituals, jazz, blues and all of their offshoots.

Two poets who have been trailblazers in the marriage of musical and poetic form are Afaa Michael Weaver and Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon. Mr. Weaver invented a sonnet-like form with refrain called Bop, which Ms. Van Clief-Stefanon has adopted and used in two of her books: Black Swan and, more recently, Open Interval. The latter contains a variety of forms, several of them music-influenced. What I like about her writing in general is that she always picks the structure best suited to the particular poem she is writing, and breaks the structure she herself has set up when it’s most effective. A word about the book’s title: although the phrase “open interval” doesn’t appear in the text of the book itself, it’s relevant for a few reasons. In music theory, an open interval (usually an open fifth) consists of two notes some distance apart, without a third note in the middle. Basically it’s a chord without its middle note, two slices of sandwich bread without the filling. It’s the sound string instruments make when tuning up, haunting and spare. An open interval, of course, could also be a blank space in time. A break between meetings. A pause in conversation. An undetermined place. Here is an interview where the poet explains her understanding and use of the term.

Open Interval‘s opening piece is based on the poet’s experience teaching at a maximum-security men’s prison in Auburn, New York. It also refers to her love of stars and astronomy, which is linked to her first name (RR Lyrae is a type of star in the constellation Lyra). In this poem, we see an unfolding of narrative and image, planned yet improvisatory. While some bop poem refrains come from African American song, this one comes from Rainer Maria Rilke.

If a bop is a jazz tune, a structure with its own artistic constraints and freedoms, it bears resemblance to a type of Baroque keyboard piece called an invention. The Two-part Inventions of J.S. Bach are short, intricate contrapuntal pieces. They can be played by intermediate-level students but sound brilliant at fast tempi played by the likes of Glenn Gould. Each invention is based on a single brief motif, and unfolds as the motif jumps from hand to hand, octave to octave, sometimes played backward, sometimes upside down. I’m tempted to see this happening in Van Clief-Stefanon’s poem “Dear John: (Invention)” but, beyond the two-line couplets, I’m not sure why she chose that word for the title. Perhaps because the motif is sound itself. The “John” whom she addresses here and elsewhere is deaf 18th-century astronomer John Goodricke.

A few years ago, Mr. Weaver held a contest to find new work for an anthology called Bop, Strut and Dance. The idea was for contributors to write poems inspired by, structured like, and/or quoting African American musical forms. Writing from outside of this culture, attempting to pay respect without appropriating, I tried my hand at a couple of poems. One of them was selected for the anthology; sadly, the book got held up in publication snarls and never was produced. Here is the poem they accepted.

Sing and Shout

It’s not all bleak and dry, depression:

this city has spires. Flashy cars

and buildings, thoroughfares; picture red

lights, metallic blue signs and neon flares.

It’s always rush hour when I try to leave,

no traffic the other way. You can get in,

day or night, under any of these portals. There’s

twelve gates to the city.

Three in the east: pogroms, displacement, death;

three in the west: the pain of everyone else.

Three in the north, three in the south: guilt so large

it’s worth traveling to see. And genes (I meet

my dad and granny there) like invisible shards.

Sun glitters on the tips of razor wire

and plane geometry of a temple square.

There’s twelve gates to the city.

Someday smuggle me out on prayers, pills

and reason. I’ll wait for you by the familiar rough

roadside, we’ll go, and stay in the country awhile.

But this metropolis has weight and pull; it shines

and groans and tries to make citizens. It’s got cops,

and they are waiting for the wandering girl; say

let us show you. Stop working and start crying.

Twelve gates to the city, hallelujah.

There are some nice versions of the gospel song that inspired the poem easily accessible online. My favorites are those by Clara Ward and the Davis Sisters, respectively. Great keyboard parts.

There’s one musical form, above all others, that suffuses our American listening vocabulary, and that is the blues. Of all forms arbitrarily designated classical or vernacular, the twelve-bar blues seems to me to have the most perfect unity and sense of inevitability. It’s like a musical glass sphere, one that can hold and reflect all aspects of the songwriter’s psyche. Written and published poetic blues goes back at least to James Weldon Johnson, and flourished with Langston Hughes. Hughes’s “Weary Blues” is a singular poem: it’s a music poem, witnessing a performance; it’s an adaptation of musical form, rendering blues tempo and cadence; AND it’s a setting-down of song lyrics in print.

Did that specific singer exist, singing those very words? Or did he slide out of Hughes’s imagination, into the spotlight of that old gas street lamp, to represent a kind of music, a kind of feeling the reader recognizes implicitly? I love the way the singer ropes in the piano, not merely as a sound-producing tool but an accomplice. Maybe an unwilling one, as the piano is made to moan not once but twice. Hughes doesn’t have to say much or explicate the black experience. The bone-deep weariness of the Negro performer is evident in every line. Here, at least, he seems to perform for his own sake–if not for pleasure, at least for catharsis. Poetic blues, like the music itself, sends our collective human memory back to the slave coffle, a reminder of the untold strength it took to survive. To make art from the materials at hand, to make black music on black people’s own terms.

Women, too, can play and sing the blues. A couple minutes of listening to Ma Rainey or Bessie Smith, or the delightfully raunchy yet proper Emma Barrett, is enough to know it’s a different thing from men’s blues. Because it’s always heartening to hear a woman reach her own conclusions at the end of the verse (right where the chords go V-IV-I-I), I’ll cite two more by Ms. Van Clief-Stefanon. This is about as concise as it gets:

Blues for Dame Van Winkle

I drove over to the Catskills

Met a woman there like me

Took a trip down to the Catskills

Was a girl there just like me—:

Not so much waitin for her man

as she was waitin to feel free

It’s funny to read/hear a blues about the Catskills, because it’s not a region of the country much associated with the blues. On the other hand, this poem refers, as many blues compositions do, to an American legend. Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle, written in the style of a fable heard and repeated second- or third-hand, and possibly based on earlier German folk tales, tells the story of the main character’s unusually long sleep and return to his village as a stranger. Dame Van Winkle, Rip’s wife, is cast as a shrew. She dies while Rip is asleep on the mountain. Since we don’t know much about her, we are free to imagine, along with the poet, Dame Van Winkle’s own side of the story. Perhaps Rip was a layabout who deserved to be nagged. Maybe she didn’t miss him all that much. Maybe she was hoping to hear some definite word of his demise, so she could live in freedom. And how weird and sadly signifying to reach back two centuries and across a racial/ethnic divide and realize–any two women could be alike in this way.

Love is equivocal. That’s true in folk tales as well as real life. And not only the love between spouses or paramours–we can also feel ambivalent about our calling in life, at times. A musician’s devoted relationship to her instrument is equivocal. Anywhere there’s passion, there is bound to be some anger. With that in mind, I’ll close this post on musical-form-as-poetic-form with one more by Ms. Van Clief-Stefanon. Unlike the other poems I’ve cited, “Maul” is not available in an online reprint, so the best way to read it would be to find a copy of Open Interval. As a stopgap, here is a citation page from a journal archive with the spacing all wrong but with the text intact.

This blues reads very much like lyrics. It’s impossible for me not to hear the harmonic progression that would go along with each stanza. It’s impossible to read it in anything other than the paced andante in which blues is traditionally sung. (The author did, at one point, perform it with guitar accompaniment at a literary festival.) But there’s something here that keeps the poem from being merely lyrics set down on a page à la Leonard Cohen. The punning of the last line, “be a hard cold fall,” as in autumn/the fall the narrator anticipates taking in the earlier line “stick with you til I fall,” is essentially a poetic device, not a songwriting one. The title, too, takes us a little out of the realm of repertoire. By pulling out a single word from the final stanza, the poet brings to our attention an image and idea that could have been easily overlooked in the final coast to the end of the verse. “Maul” is both noun and verb. In the poem’s text, the narrator instructs the unnamed man to bring his maul in order to split her firewood. Subtext: bring his something to split her something. Context: his imminent departure, and maybe the whole of their relationship, will leave her feeling bruised, beat up. There’s no indication that the man acts violently–merely that the narrator experiences both his love and its loss as a blow.

That’s as a good a segue as any to the next post, where we’ll explore the idea of music and poetry as consolation.