“Rummaging into his living, the poet fetches the images out that hurt and connect.” W.H. Auden, The Composer

“Evil often stops short at itself and dies with the doer of it; but Good, never.” Charles Dickens, Our Mutual Friend

Collaborative piano is the best job in the world. I get to play gorgeous, challenging music while supporting and learning from other musicians. By choice and by happenstance, choral music has become a sub-specialty of mine. I’m not much of a singer, but if you are a choral director, I am the accompanist you want to hire. At present I am preparing the Mozart Requiem with the director I have worked most closely with over the last decade. Her large, multi-lingual, musically sensitive high school choir is up to the task of singing this meaningful work. And I like to think I’ve risen to the task of playing the orchestral reduction. We’ll be performing portions of the Requiem for the community this week.

If you’ve never been immersed in European choral music or Catholic musical tradition, here are the basics: many famous classical composers wrote music for mass. Some wrote specifically a requiem, which is a setting of the mass for the dead (“requiem” translates as “rest”). The text comes from Catholic liturgy; there are several sections, in Latin mostly, with a little Greek. All of the composers wrote their own music for the text, and the music varied a lot by time period and personal style. So Mozart’s setting from 1791 sounds very different from Fauré’s, composed one hundred years later.

Mozart’s Requiem is extra poignant because he died composing it. He accepted a commission to write it, found himself in failing health, and got eight bars into the Lacrimosa before his life ended. The work was completed by Franz Süssmayr, a protégé, at the request of Mozart’s wife.

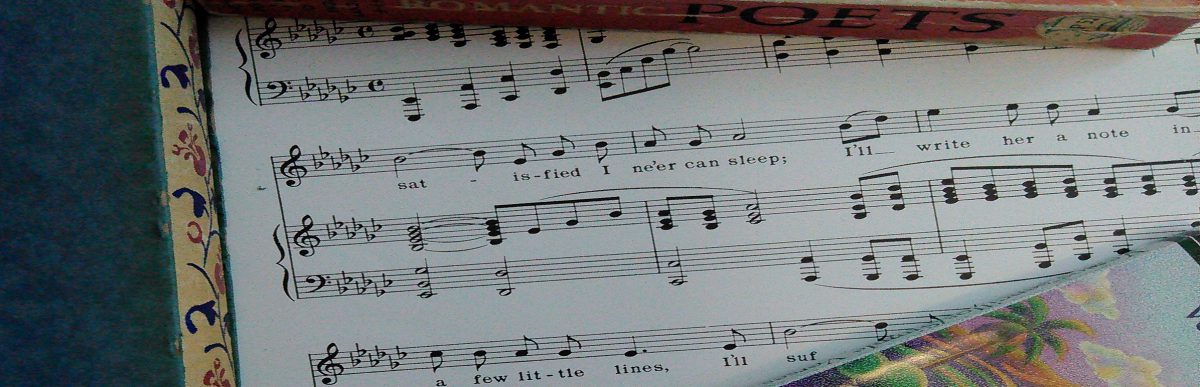

While the Lacrimosa is perhaps the most famous sub-section in the whole work, and the Dies Irae probably the most impressive, it’s a different part that stays in my head after each choir rehearsal: the Confutatis.

Without knowing a word of Latin, you can hear in the music alone that something scary is going on, followed by something calm. If you read the text, the parts that Mozart set to scary music have to do with the condemnation of the damned. The calm parts are the ordinary folks’ souls imploring, “Call me, call me among the blessed.” A separation is going on: it is the day of wrath (“dies irae”) and humanity is being sorted. The last section of Confutatis is quietly haunting. There’s an image of the speaker’s heart turning to ashes. And there is the beseeching line, “Help me in my final hour.” No wonder Amadeus became a hit movie; the drama writes itself.

I’m not Catholic or, for that matter, religious at all. I appreciate the mass as poetry. I’m sort of a humanist agnostic, more concerned with how we treat each other on earth than what happens in a mythical apocalypse. That doesn’t mean I don’t think about issues of life and death. It so happened that, as I was working up the score for our upcoming concert, a spate of school shootings occurred. The most deadly was the rampage at Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

When tragedies occur that shouldn’t…when I am powerless to help people in deep mourning…when a response is called for and no amount of practical actions will suffice…that’s when I go to the piano or to the page. I started writing a poem about Confutatis because the music reached me. And it will always stop me in my tracks to realize that Mozart died younger than the age I am now. Parkland wasn’t on my mind—consciously—as I wrote notes for the poem. I didn’t realize until the poem was almost finished that it was going to be about my sacrilegious response to gun violence. It’s a truism that people who have been through a tragedy either cling more tightly to their faith or give it up altogether. Each time I find myself a witness to someone else’s life-altering tragedy, I become less inclined to believe in the omnipotent, personally caring god of Western monotheism. Simultaneously, I become more stubbornly attached to the idea that we will ultimately save each other. I have hope because of the student activists working to preserve their own safety.

| Confutatis (Mozart Requiem)

homage to Parkland

|

| When is it the wicked will |

| be silenced, confounded, or doomed |

| depending on translation? Why |

| must we wait till then to be counted? |

| Call me now. Call today with |

| some good news, unconditional. |

| Speak to us the way we speak to you.

|

| How many hands has |

| this music been through? Sorry |

| I asked. A copy of a copy |

| of a manuscript starts to look like |

| ashes. Like, almost. Nearly. |

| Near enough to ashes to count. |

| Contrite as if. Contrite as/like. That’s |

| where the page cuts off. Call |

| me when you have something to say. |

| Speak to us as if you were our god.

|

| How could the composer stop |

| living, scoring, mid-mass, leaving |

| a student to finish the job? Expired |

| over the page whereon “help me.” How |

| could any of us? Yet they will. Finish. |

| Don’t speak to me until you answer them. |

| Before this movement there will be |

| judgment; afterward, lilting tears. |

| Tell you what, don’t call me among the blessed. |

| Don’t call me at all. |

| Speak for yourself; I cannot hear you. Like the rest of them you died young and scared. |

Did the purported son of god ever despair? Jesus died at the hands of attackers around the same age Mozart died of natural causes. According to the spiritual, he didn’t say a mumbling word. It’s natural that Mozart, in extremis, would cry out—either literally, or through his music—for divine help. The men’s voices declaim the terrible fate of the damned; the women’s voices ask for mercy. Finally, all parts come together in abject humility. In the Germanic Latin in which this piece is sung, the word for ashes (“cinis”) is pronounced “tzeenees.” It has a certain crackle. The hard consonants and rounded vowels of “gere curam” express a calm resignation. It’s a cry for help without expectation of an answer. It is the acceptance of death as inevitable.

What I don’t view as inevitable is the enacting of some rigidified plan in which human will takes no part. Hence the irreligiosity. Where help is needed, we must provide it or let the supplicant go without. I believe in the act of asking for what we need, but not begging. If help isn’t forthcoming, it’s time to form a strategy and provide for ourselves.

In the poem “Alms,” by Idea Vilariño, the speaker craves help and attention so badly that she will settle for a “dirty dirty crumb.”

Each time I read this short poem, I change my mind about it. Is it sincere? Is it satirical? Is it a portrayal of a viewpoint we all can recognize, having found ourselves abased or without hope sometime in our lives? Or does the poem inspire us to say that we, in contrast to the speaker, will not settle for mere crumbs? I’m still going over and over it. “Alms” happened to be published the week I was finishing “Confutatis,” and it was like reading a sympathetic note from a fellow poet.

As I write, students in many cities are walking out of their classes in protest of the fact that they are unsafe where they learn. Large companies are raising the required age to purchase guns. The high school where I work, a high school where everyone sings, is performing a mass for the dead in the quiet comfort of our small auditorium, and we’re thinking of the lost. The age-mates, the younger-thans, the what-would-she-have-achieved-ifs.

I watch these students sing about such dire things, happily so distant from their lived experience. Prior to the Confutatis, we hear a prophecy of judgment in the Dies Irae. In an odd admixture of Old Testament and ancient Greek lore, we hear that both David and the Sibyl have foretold the burning of the world. Even a skeptic like me takes pause to wonder whether it will come to that—how much destruction, after all, must we witness before heeding the warnings filling our ears? We have been warned. We grieve with the grieving; we are as sorry as our hearts can bear, and then some. We are collectively contrite, because even those of us who avoid guns, or who own and use them safely, haven’t done enough to protect the innocent.

There is no pause between Confutatis and Lacrimosa. The music is marked “attacca,” go right on. There is a brief tension chord, an A7, before the sweet and tenebrous tones of D minor usher us into collective mourning. I want there to be more space than that. I want a large caesura, a moment for Mozart to write his will and collect his payment for the Requiem. In that imaginary pause, I want an intake of breath much larger than that allowed by a quarter rest. I want to avoid the Lacrimosa altogether. After all, there are six more sections of music to come. Scholars believe Mozart left only sketches, and Süssmayr wrote most of this material himself. And I say, so what? It is where the hope lies. Of course our students will pick up where we left off. Rightfully so. May they not face our obstacles, our intransigence, our hidebound insistence on mere good and evil and divine intervention. Their universe is so much more frightening and glorious than that.

Thank you for this beautiful, poignant commentary. To answer a question you posed, Christ did cry out in his final moments. According to the New Testament, at the end of his trial on the cross, the son of god cried out, “My God, my God! Why hast thou forsaken me?” Perhaps like so many who have cried out to that same god before and since, he felt his cries echo in a void. Christianity promotes the interpretation that his final test MUST have been faced alone. There was something noble and necessary in being abandoned in those last moments.

Your comments on the poem, “Alms,” resonated with me as well. After our little Daniel broke his leg, just days after learning how to walk, we encountered a family from our church at a Boston Market. It was Christmas Eve. I was 4 months pregnant, and overwhelmed with tending to a broken toddler, and a rambunctious 3 year-old. Boston Market was to be our Christmas dinner. But by the time I got there, no meat was left. All that was available were a few sides. Why they didn’t just close up shop, I don’t know. Maybe because this family was lingering over their meal. Anyway, as we chatted with this family, we informed them about what we were enduring at the time. They expressed concern, and asked if the church had been taking care of us. I said no, since most people at the church had no idea we had suffered an injury. Then, the father began to lecture me on the importance of allowing people to serve us, so they could get blessings. Ok. After retreating to the counter, but realizing there was nothing worth buying, we resolved to get pizza. To my horror, I turned around to find this family scraping their leftovers into carryout boxes, and insisting that we take their half-eaten table scraps for our holiday meal. After the lecture I had just been given, I had no option but to take the offensive, saliva-tainted slop, with a smile on my face, and gratitude dripping from my tongue. It was the first time in my life where I felt like I was the last thing taken into consideration for the “service” rendered to me. I did NOT need those particular “dirty crumbs.”

LikeLike

Wise, you

LikeLike